The Arsenal of Exclusion & Inclusion, written by Interboro—a New York-based architecture, planning and research collective—is an encyclopedia of policies, practices, and physical artefacts deployed in American cities to regulate access. This comprehensive guide balances historical and contemporary examples, examining both overtly exclusionary tactics and subtle mechanisms of control. Organised alphabetically, each entry or ‘weapon’ is enriched with contextual commentary through ‘voices from the battlefield’ or additional readings sidebars, while thoughtful cross-references weave connections throughout the work.

A central theme that unifies the book is how profoundly our built environment bears the legacy of a highly discriminated history. Cities, far from developing organically, have been shaped by deliberate policies designed to maintain segregated, racialised urban landscapes. The starkest examples include the Jim Crow law that mandated segregated facilities under the guise of ‘separate but equal,’ redlining practices that used government-commissioned security maps to deny federal mortgages to neighbourhoods where people of colour lived, and racial deed restrictions that explicitly prohibited property sales to non-Caucasians. These policies systematically excluded minorities from the suburban housing boom that helped millions of white Americans build intergenerational wealth.

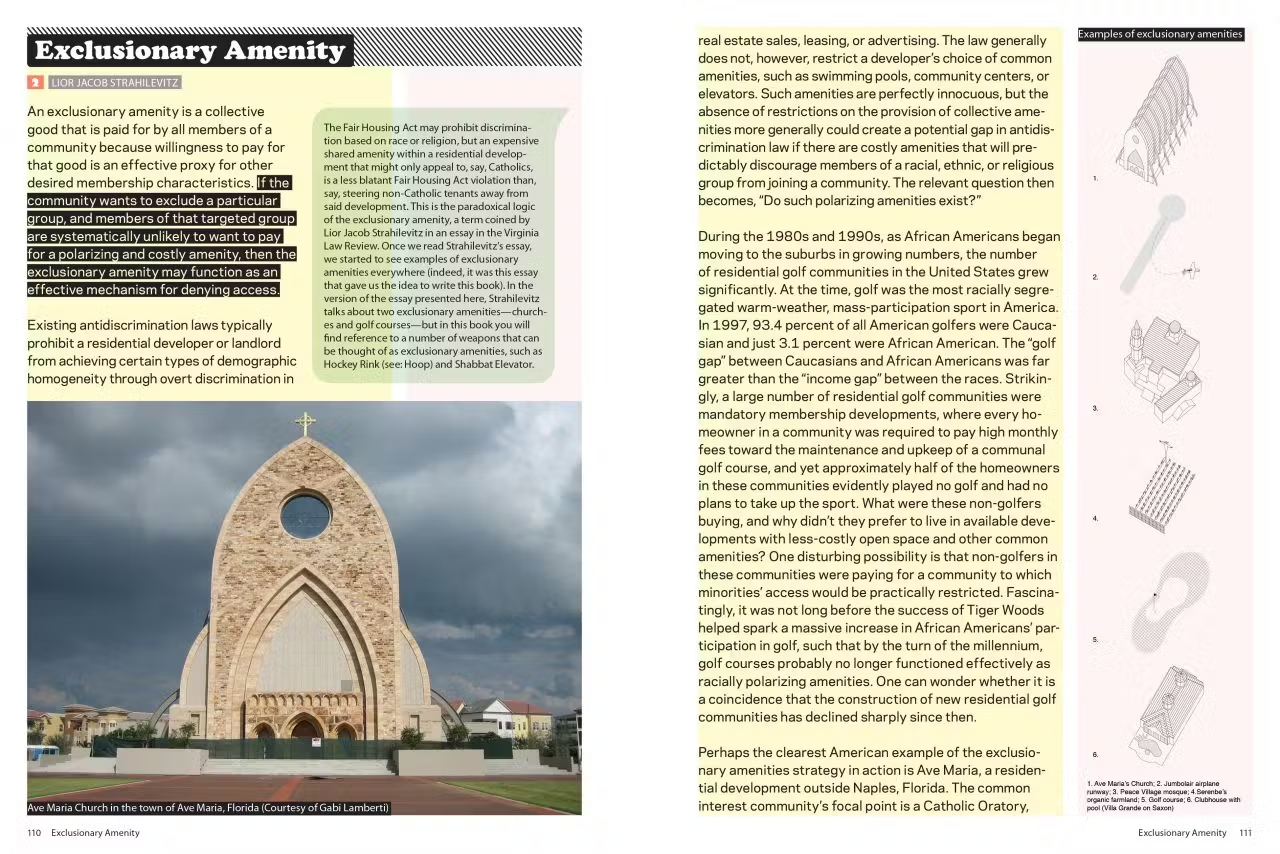

While the Fair Housing Act of 1968 officially prohibited discrimination based on race, religion, sex, national origin, familial status, and disability, contemporary forms of exclusion persist through more subtle means. As Armborst, D’Oca, and Theodore (2017, p. 11) observe, contemporary discrimination often “uses lifestyle characteristics as a proxy for race or class”. For example, the definition of family and residential occupancy standards does not explicitly mention race or class, but nonetheless creates barriers for non-nuclear families, who are more likely to be non-white populations. Whether having a basketball or a hockey field, having a golf course or equestrian centre does not explicitly prohibit access, but does communicate the message of who the community desires to have. The preference for single-family, low-density zoning, coupled with restrictions on apartment size and single-occupancy units prevents the less wealthy from accessing affordable housing. Though many of these policies adopt a public health or property value rhetoric, they effectively preserve homogeneous communities and prevent social mixing.

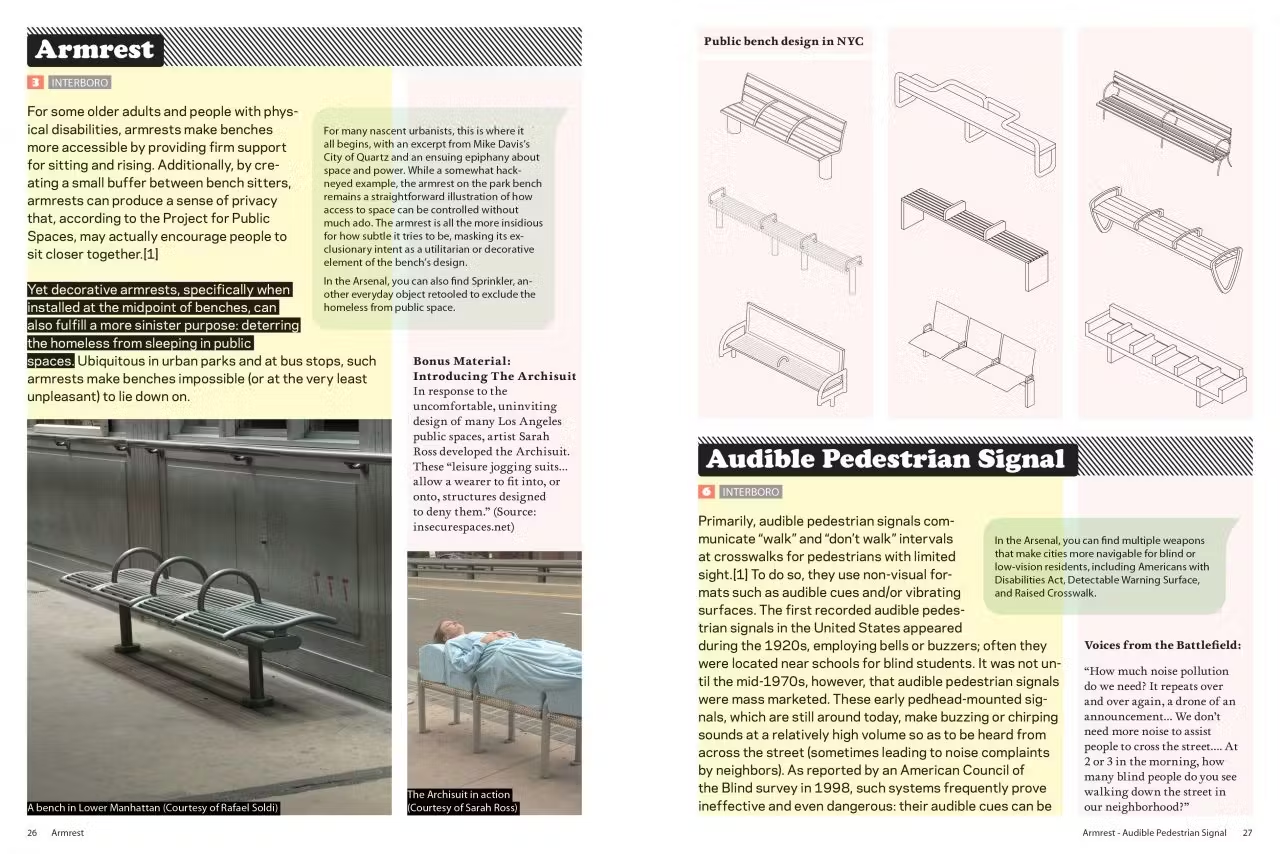

The regulation of public spaces emerges as another crucial theme, revealing a stark contradiction between ideal and reality. While public spaces are theoretically meant to be freely accessible to all and foster tolerance of difference, exclusionary measures are almost ubiquitous. And since its exclusionary or inclusionary nature is relative to the subject, many of them go unnoticed or unquestioned by those who are not targeted (Rosenberger, 2020). Ultrasonic devices that repel young people go unnoticed by older adults; decorative bench armrests that seem aesthetic to casual users actually serve to prevent the homeless from resting. Through such examples, the book prompts us to confront uncomfortable questions: At what point does casual gathering become criminalised loitering? How do aesthetic preferences transform into moral judgments that mark certain groups as public nuisances?

Although these “weapons” ostensibly serve public safety, aesthetics, or local interests, they also have the intention to manage the “undesirable”—whether non-conformative behaviours or the presence of certain social groups. Many of the examples in the book provide testimonies to the scholarly discourse on the increasing privatisation and commercialisation of public spaces. Goldberger (1996) attributes this phenomenon to the proliferation of consumerist culture and the rise of the suburban, which has spawned a new urbanism offering sanitised “public spaces” that package city life into “a measured, controlled, organised kind of city experience” (p. 147). These curated environments prioritise marketability over genuine public access—any exposure to poverty, crime, or even perceived incongruity risks disturbing customers’ comfort. The resulting interventions, from explicit regulations to subtle design elements, merely displace social issues rather than resolve them (Atkinson, 2003).

The catalogue of exclusionary and inclusionary tools raises a critical question: who wields the power to claim and control spaces? The concept of ‘spatial capital,’ first developed by French geographer Jacques Lévy, provides a useful analytical framework. Lévy defines spatial capital as “the set of resources, accumulated by an actor, enabling her/ him to engage with place and space, to profit, in accordance with her/his strategies, by the use of the spatial dimension of society (Lévy, 2013, cited in Rérat, 2018, p. 104)”. This power to “take–and make–place (Centner, 2008, p. 198)” extends beyond physical control of space to include perceived entitlement to spaces. As with other forms of capital, spatial capital is unequally distributed among members of society, and its actualisation of some groups can result in the exclusion of others (Centner, 2008; Lévy, 2014; Rérat, 2018). The book’s examples repeatedly demonstrate how families with children, people experiencing homelessness, youth, non-residents, and people of colour are systematically excluded from ‘public’ spaces. This geographic marginalisation compounds social exclusion, creating barriers to accumulating other forms of capital essential for social mobility.

Overall, this book presents a wide collection of planning tools that have shaped the physical and social landscape of American cities. By incorporating diverse perspectives beyond the authors’ own analyses, the book illuminates the complex and often contested nature of these urban interventions. While firmly grounded in historical analysis, it ultimately serves as a call to action, challenging readers to envision more equitable and inclusive cities. Rather than a book of urban theories, the short portfolio format for each case, together with the extensive use of visuals (maps, photos, diagrams) renders it accessible for urban practitioners or anyone enthusiastic about urbanism.

Reference:

Atkinson, R. (2003) ‘Domestication by Cappuccino or a Revenge on Urban Space? Control and Empowerment in the Management of Public Spaces’, Urban Studies, 40(9), pp. 1829–1843. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098032000106627.

Centner, R. (2008) ‘Places of Privileged Consumption Practices: Spatial Capital, the Dot–Com Habitus, and San Francisco’s Internet Boom’, City & Community, 7(3), pp. 193–223. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6040.2008.00258.x.

Goldberger, P. (1996) ‘The rise of the private city’, in R.F. Wagner and J. Vitullo-Martin (eds) Breaking away: the future of cities: essays in memory of Robert F. Wagner, Jr. New York: Twenthieth Century Fund, pp. 135–147.

Lévy, J. (2014) ‘Inhabiting’, in The SAGE Handbook of Human Geography: Two Volume Set. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, pp. 45–68. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446247617.

Rérat, P. (2018) ‘Spatial capital and planetary gentrification: residential location, mobility and social inequalities’, in L. Lees With Martin Phillips (ed.) Handbook of Gentrification Studies. Edward Elgar Publishing. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4337/9781785361746.00016.

Rosenberger, R. (2020) ‘On hostile design: Theoretical and empirical prospects’, Urban Studies, 57(4), pp. 883–893. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019853778.