During my formative years, the job of “university lecturer” was always praised by my relatives as the perfect career—especially for women.

“What a great job: it’s respected, easy, comes with winter and summer breaks, offers stability, and even provides benefits for your children’s education!”

This neatly sums up the popular perception of academic employment. On the one hand, it’s like holding an “iron rice bowl” (a guaranteed, lifelong position, 铁饭碗 in Chinese), and on the other, there are perks such as visiting scholarships, international conferences, and paid academic sabbaticals (in the United States, once you have tenure, you can take a sabbatical year every seven years). It would seem there’s little for university faculty to complain about.

However, one doesn’t have to look far to come across news of “young lecturers dying from overwork,” “adjunct faculty striking in protest of low pay and minimal benefits,” or “Trump’s proposal to slash funding for the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH).” These days, teaching at a university appears to be far from the easy, stable profession people once imagined.

Silent Scholars

Rosalind Gill, in her book Silence in the Research Process: Feminist Reflections1, notes that academics often experience feelings of exhaustion, overload, insomnia, anxiety, shame, hurt, and guilt—emotions that are “at once ordinary and everyday, yet at the same time remain largely secret and silenced in the public spaces of the academy (p. 229).”

Social scientists often focus on precarity, emotional burdens, and inequality in other professions, yet rarely reflect on the conditions in which they themselves work. This tacit understanding, seldom openly discussed, has multiple causes.

Compared to other sectors, academia does indeed retain a certain level of privilege. Faced with more severe hardships elsewhere, airing one’s own grievances may feel like wallowing in self-pity. But if we can only talk about the most extreme forms of injustice and suffering, does that mean all smaller-scale issues are off-limits for scrutiny? If we remain silent about our own situation merely because “others have it worse,” many power structures and social problems risk being overlooked.

High pressure and instability in academia seem to be taken for granted: if you choose this path, you must endure these trials, and anyone who can’t withstand the pressure will naturally be eliminated. Once this unhealthy model is regarded as an individual burden, the proposed fixes might be limited to training in time management, speed reading, and so on—further extracting every bit of surplus value rather than examining what might be flawed in the system itself.

I’m still a doctoral student, not yet formally on the academic career track. But as someone for whom this might be a future path, I see plenty of examples around me: from those in adjunct or temporary positions, to those fighting their way along the tenure track, to people who already have tenure. Their daily lives and life choices are strongly shaped by this line of work. Although no job is absolutely secure, the instability in academia stands in stark contrast to the traditional notion of a “guaranteed post”—an incongruity that leaves many who work in these roles feeling deeply conflicted.

The Uberfication of Higher Education

The discussion here concerns academic workers in a broad sense—individuals who, after earning a PhD, might become postdoctoral fellows, research assistants, university instructors, or administrative staff.

When we were students, we probably knew little about the specific employment contracts our lecturers had. Their offices all looked similar, and their teaching responsibilities appeared much the same. We tended to address every instructor as “professor,” even though most had not actually attained that rank. In truth, a large proportion of university faculty are neither tenured nor on a tenure track. Instead, they are hired under either temporary, hourly-paid arrangements (with no other employment benefits) or fixed-term contracts (ranging from a few weeks to several years, with benefits resembling those of long-term employees but subject to time limits).

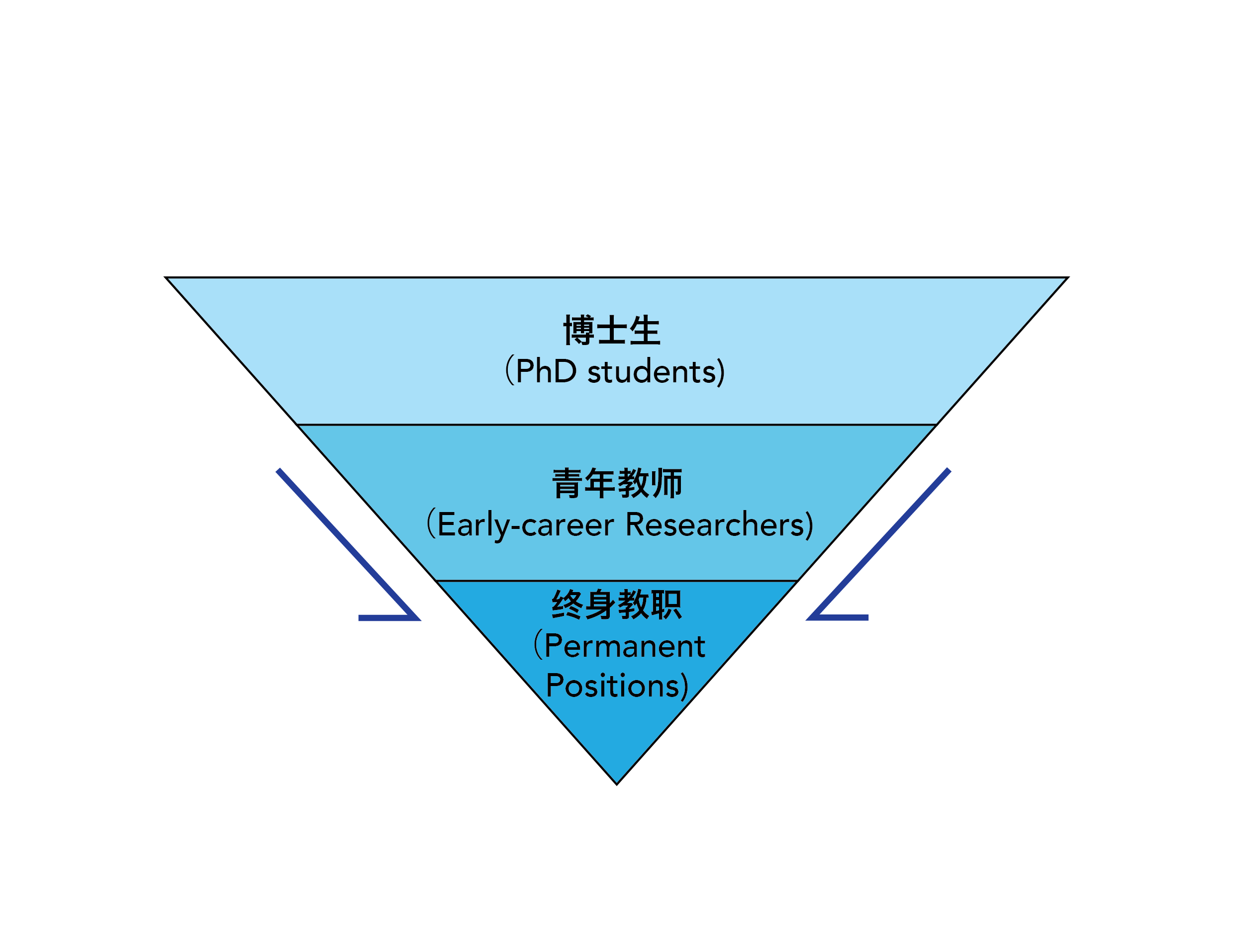

A National Science Foundation (NSF) report shows a steady year-over-year increase in the number of people awarded doctorates, while the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) has noted a decline in the proportion of tenured and tenure-track positions relative to non-tenure-track roles. From the outset, the academic career path has a funnel shape—starting with doctoral students, then moving to early-career researchers, and eventually to tenured faculty. As the number of PhDs steadily rises while tenure positions become scarcer, that funnel narrows even more dramatically.

The dwindling supply of tenured positions has led universities to rely heavily on contingent appointments (including part-time adjuncts and full-time non-tenure-track roles). AAUP data indicate that more than half of U.S. university positions are now part-time, comprising adjunct instructors, lecturers, and graduate teaching assistants. Currently, around two-thirds (68%) of academic workers in higher education hold contingent roles, while only 24% are tenured or on the tenure track. By contrast, 30 years ago, the ratio was closer to a 50–50 split.

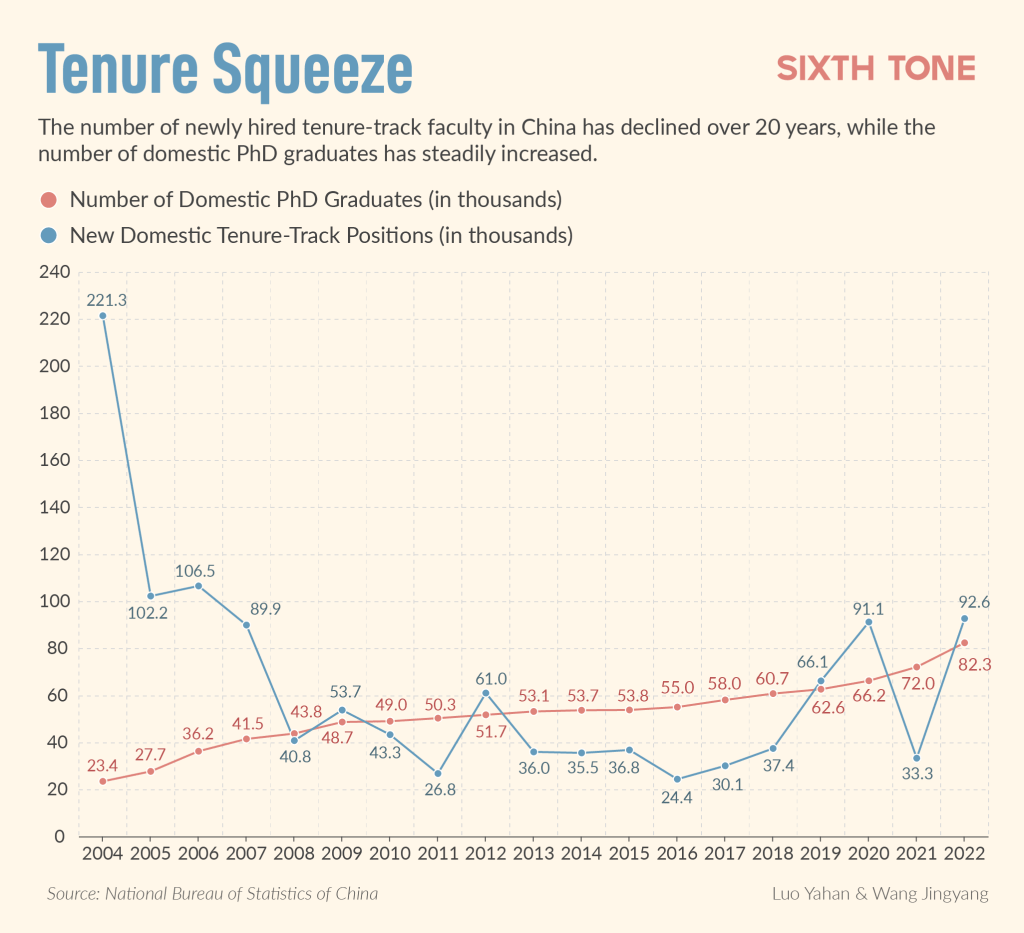

According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, in 2004, the number of newly added tenure-track positions (221,300) vastly exceeded the number of new PhD graduates (23,400). Yet this advantage disappeared rapidly after 2007. Since 2010, the yearly count of PhD graduates has risen sharply, while the increase in tenure-track jobs has remained relatively low. By 2016, the number of PhDs (55,000) was almost double the number of newly added positions (24,400), forcing many doctorate holders to move into non-academic fields or short-term contract roles. Factoring in the returning PhDs who studied abroad only intensifies the competition.

(Source: Luo Yahan and Wang Jingyang, Sixth Tone)

University administrators often frame part-time and temporary teaching roles as a means to achieve “flexibility” and “balance.” However, a 2020 American Federation of Teachers survey reveals that most adjunct instructors have highly insecure employment. A third earn less than $25,000 a year (below the federal poverty line for a family of four), fewer than half receive employer-provided health insurance, and 41% face so much job uncertainty that they often don’t know until one month before the semester starts whether they’ll be teaching at all.

The disappearance of this “iron rice bowl” extends well beyond academia. With changes in the global economic structure, advances in technology, and a rising demand for labor market flexibility, a wave of “gig economy” work has spread worldwide. Powered by digital platforms, people have shifted from traditional, long-term full-time employment to short-term, temporary, freelance, or contract-based work. On the plus side, gig workers can choose when and where to work, but they also lack traditional job protections. Because the pay is often low and unstable, many must juggle multiple jobs—embodying what’s sometimes called the “slash career.”

The gig economy’s influence is not limited to blue-collar or service-sector workers; knowledge workers—such as researchers, lecturers, journalists, designers, and programmers—have been similarly affected. Robert Ubell, Vice Dean Emeritus of Online Learning at the NYU Tandon School of Engineering, refers to this phenomenon as the “Uberfication of Higher Education,” wherein universities increasingly rely on low-wage, precarious, short-term faculty, much like the gig-economy model.

Many new PhDs are unable to secure permanent academic positions and must rely on short-term contracts, adjunct roles, or external funding, applying for one job while holding another, hoping eventually to land a stable appointment. This precarity is not only an economic and political hallmark of neoliberalism but has also become a lived reality and way of life2.

The Precariousness of Tenure

Even for those who successfully land a tenure-track position, true job security remains out of reach. For the fortunate few who do secure a spot on the tenure track, the “iron rice bowl” is still a long way off.

In 1940, the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) issued its Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure, stipulating that the probationary period for assistant professors generally should not exceed seven years (in practice, many universities use a six-year “clock”). This system was originally intended to foster young scholars’ research ambition and creativity, while allowing faculty the security to pursue academic freedom. Academic research often clashes with commercial or political interests; the tenure system means that professors, under the protection of secure employment, can conduct their work relatively free from external interference, thus preserving academic independence. With tenure, faculty also have more freedom to pursue riskier, more uncertain—yet highly innovative—research topics.

In reality, however, the tenure track makes assistant professors some of the busiest people in academia. They must produce high-impact research in a short time, while juggling teaching duties, grant applications, and service to the academic community—leading some, once they’ve secured promotion, to “lie flat” for a while to recover from long-term burnout.

During China’s planned-economy era, universities operated under a “staff establishment” (编制制) model, in which faculty positions were akin to an “iron rice bowl.” In the 1990s, some Chinese universities began experimenting with reforms inspired by the American “pre-tenure to tenure” system—often termed “up or out.” By 2020, of the 42 universities recognized as China’s top-tier institutions, 34 had adopted a tenure-track system, comprising 80% of these schools.

However, unlike the U.S. approach, many Chinese universities do not follow a strict rule for promotion. Although contracts often specify benchmarks—such as publishing a certain number of core-journal articles over a set period, securing national or provincial-level grants, or fulfilling teaching and administrative tasks—in practice, it’s rarely “one slot for one person.” Instead, institutions recruit multiple people for the same job and let them compete with each other. This competitive setup creates higher pressure among colleagues and weakens the sense of an academic community. The six-year clock also continues to tick regardless of major life events, such as pregnancy and childbirth, forcing many junior faculty to postpone personal plans or work overtime to make up for lost time—leading to excessive fatigue.

In recent years, global financial pressures on universities have cast doubt on the absolute security of even those who’ve achieved tenure. Except in cases of serious misconduct, universities generally cannot dismiss tenured professors at will, but mass layoffs are possible in severe financial crises, including shuttering entire departments or, in extreme cases, the institution itself. I’ve seen examples of associate professors with strong academic records and considerable respect on campus who, despite their accomplishments, could not advance to full professor. Their only option was to move abroad or switch universities to achieve promotion elsewhere.

The Cost of Academic Mobility

Academic mobility seems to be an essential skill for career development in this field. Many universities have an unwritten rule that their own PhD graduates cannot immediately apply for faculty positions at the same institution; candidates must first prove themselves elsewhere before they can return. The prevalence of short-term contracts, coupled with a shrinking number of available positions, makes the competition even fiercer. An ideal candidate is expected to be unattached, flexible, always prepared for scrutiny, and willing to do more for less pay.

Much of the discussion about academic mobility focuses on the global flow of talent—both loss and return—while overlooking how this instability affects one’s personal life, family, close relationships, and emotional well-being. Choosing an academic career often means frequent relocations, long periods of separation from partners, and the postponement of other important life decisions such as buying a home, getting married, or having children. With modest salaries, many early-career academics also depend on additional support from family or partners for an extended period3.

In the near future, as artificial intelligence gradually replaces much of the basic teaching work in higher education, positions such as research assistants and postdoctoral fellows may be cut in the name of “cost reduction and efficiency.” This would only exacerbate the inherent instability of academic work. One can’t help but ask: Has the “iron rice bowl” of academia become a thing of the past? Should we reexamine and restructure academic careers and incentive systems in response to these challenges?

Personal and Institutional Dilemmas

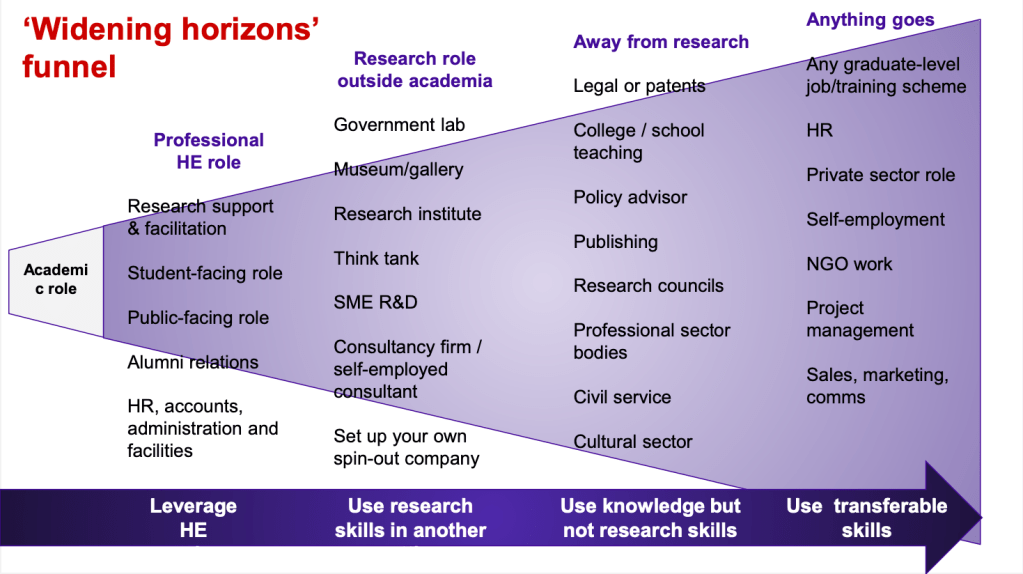

In recent years, many universities have emphasized “transferable skills”—such as project management, innovation, time management, communication, and problem-solving—in their doctoral training programs. From day one of a PhD program, it’s made clear that most of you will not stay in academia for the long haul. If you ask a classroom of doctoral students who is absolutely certain about staying in academia or absolutely certain about leaving, you’d only see a few hands raised. The reality is that most people are in a gray zone: hoping to find work related to their research topic or methodology, yet lacking the confidence to commit firmly to one path.

Alongside hearing about the “narrowing funnel” of academic opportunities, we’re also told about the “widening horizons funnel” that awaits us if we leave academia—one that presumably expands our options. From university administration roles, to research positions outside academia (e.g., in research institutes or think tanks), to work that leverages your knowledge but doesn’t involve research, or even any job whatsoever (like opening a café)—it seems the world is your oyster, so long as you refuse to be hemmed in by your degree.

Yet for someone who has spent years pursuing a doctorate, taken multiple short-term contracts, and in the end chooses a position that “doesn’t require a PhD,” that choice might be tinged with resignation, relief, or even a certain sense of shame. Was the time and effort worth it? Were all those late nights, academic papers, and piles of research literature in vain? If you ultimately land in a role that a bachelor’s or master’s graduate could have filled, why devote so many years to a PhD? We shouldn’t overlook the very real confusion and anxiety people feel when grappling with such questions.

Of course, we should encourage doctoral students and early-career researchers to let go of the belief that “academia is everything,” to demystify academic careers, and to explore broader life possibilities. I can convince that the true value of a PhD doesn’t lie in whether I remain in academia; it’s found in the journey itself—a solitary yet profound process of self-exploration, a deep conversation with knowledge, with myself, and with the world. In a sense, it can be seen as a luxurious experience.

“Flowers can bloom again, but youth does not return. (花有重开日,人无再少年)“

Individual dilemmas may be mitigated by shifts in mindset or personal acceptance, but that doesn’t excuse the fundamental flaws in the current system. Behind the Darwinian logic of “the survival of the fittest” in academia lies the struggle and compromise of countless individuals and their families. Jobs in academic have become as precarious as any other job, and the ivory tower is no shield against the gig economy. Yet these gig-like positions are still—quite paradoxically—viewed as an “iron rice bowl.” That contradiction underpins the unique challenge of this profession.

Footnote:

- Gill, R. (2009) ‘The hidden injuries of the neoliberal university’, in Gill, R. and Ryan-Flood, R., Secrecy and Silence in the Research Process : Feminist Reflections. 1st edn. Oxford: Taylor & Francis Group. ↩︎

- Berlant, L. (2011) Cruel Optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

↩︎ - McKenzie, L. (2022) ‘Un/making academia: gendered precarities and personal lives in universities’, Gender and Education, 34(3), pp. 262–279. ↩︎

Leave a comment