一个准博士的开题报告

A few days ago, I came across a meme suggesting that the happiest time for a PhD student is the summer before starting their doctoral studies. During this time, you can proudly announce to everyone, “I’m going to start my PhD!” and receive their blessings without actually having to do anything yet. It’s similar to the summer after the college entrance exams.

I think I’ve already passed that stage… Now, I need to be prepared to answer one question in various situations: “What’s your research topic? How’s your research progressing?” In reality, I can’t understand most of my classmates’ research topics, and I assume the same is true for them about mine. So this question has become a form of small talk, similar to asking, “Have you eaten yet?” Whether you’ve eaten or not doesn’t really matter; I’ve fulfilled my academic etiquette by asking. We can then reflexively respond with an “Ah, sounds interesting” and move on to discuss other things.

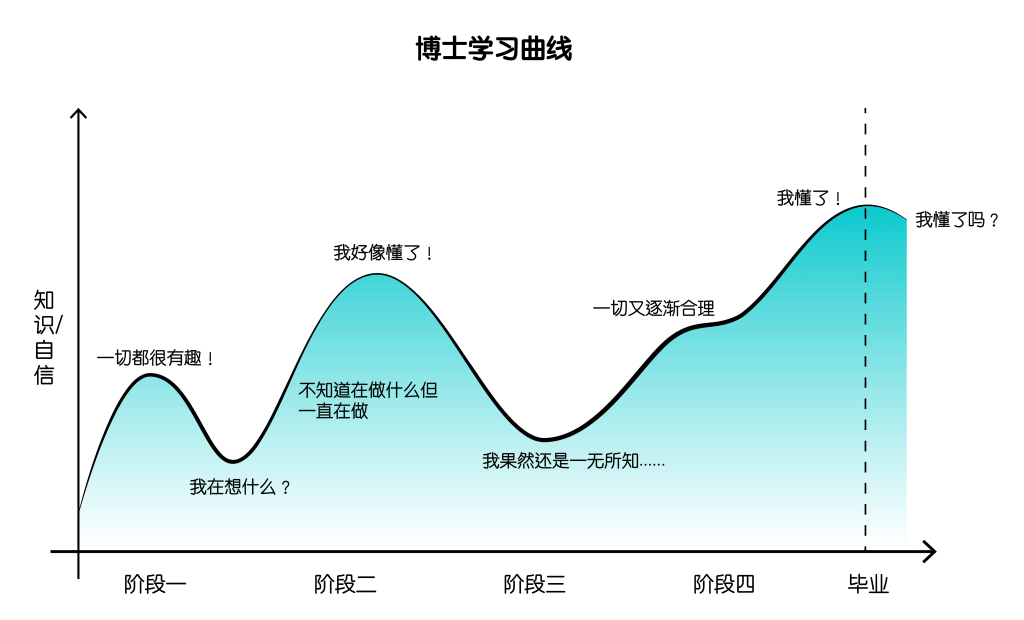

“What’s your research topic?” is a soul-searching question that every PhD student experiences daily. Its impact depends on which stage of the learning curve the student is at. When you’re confused about your research and worried about its prospects, you dread being asked. But when you have some results, you want to share them with the whole world (although probably only a few people are willing to listen). The answer to this question is constantly changing and remains uncertain until you write the final acknowledgments and abstract of your dissertation.

The charm of the summer before starting a PhD might lie in the fact that it’s a period when you can maintain fleeting relationships with all possibilities. However, once you begin your research, you gradually have to commit to a monogamous path, constantly defending your choices and praying that things won’t develop to the point of “divorce.”

During this summer, I provided an answer to this question in the form of my master’s thesis. But apart from my supervisor, no one is going to read that thesis, and even I don’t really want to look at it again after finishing it……After taking a break for a few days, I decided to answer this question in more accessible language. Before presenting my conclusions, please allow me to use the following three vignettes as an introduction.

中文

前几天看到一个梗图,说是博士生最开心的时候就是开始读博前的暑假。因为你可以告诉所有人“我要去读博啦!”,得到大家的祝福然而却不用开始做任何事情, 类似于高考之后的暑假。

我可能已经过了那个时段了……现在的我需要在各种场合准备好回答一个问题:你的研究课题是什么?你的研究进展如何?其实大多数同学研究的课题我并听不懂,我猜反之亦然。于是这个问题就成了一个“寒暄”,类似于“您吃了吗?”吃不吃的不打紧,反正我已经尽到了我的学术礼仪,条件反射般地回应一个“啊,听起来很有趣(sounds interesting)”,我们就能开始谈谈别的事儿了。

“你的研究课题是什么”是每一个博士生日常经历的灵魂拷问,其伤害值取决于该博士生在学习曲线的哪一个阶段。在研究一头雾水、前景堪忧的时候就怕别人问,但是在有点成果的时候恨不得跟全世界分享(虽然全世界大概只有几个人愿意听)。这个问题的答案是不断变化的,在写下最终论文的致谢和摘要之前都无定论。读博之前的暑假的魅力可能就在于,那是一个允许和所有的可能性都维持露水情缘的时期,然而开始研究之后就得慢慢走上一夫一妻制的道路,不断为自己的选择辩护,祈祷事态不会发展到离婚的那一步。

在这个暑假里我以硕士论文的方式给这个问题提供了一份答卷。但是这论文除了我的导师肯定是没人看的,甚至我自己写完也不太想看……闲下来几天我又翻开这个尘封一年多的公众号,决定用更通俗的语言回答这个问题。在给出结论前,请允许我用下面三个片段做个引子。

1 | A Chinese Restaurant in Eugene

In the fall of 2013, I went abroad for the first time, exchanging at the University of Oregon in the United States (where Daniel Wu graduated). The university is located in the small town of Eugene, Oregon, famous as the birthplace of Nike and for the Oregon Ducks, the university’s football team mascot. The school’s official website even proudly proclaims, “We Are Ducks.” The student dormitory I was assigned to during the exchange didn’t have a kitchen, and there weren’t many Chinese restaurants on campus, so I mostly survived on salads with teriyaki tofu or chicken breast from the cafeteria downstairs.

On an ordinary weekend, I took a bus ride of nearly an hour to reach a Walmart in the suburbs. The world outside the campus felt like a vast wilderness, with no city, no pedestrians, just large cornfields connecting the school to civilization centers like Walmart. What I didn’t know was that the town’s weekend bus service ran only once an hour. After finishing my shopping, I had just missed the previous bus and was forced to reluctantly return to Walmart for another 45 minutes of browsing. When I came out again, I was fortunate enough to catch the next bus. However, by the time I reached the school, night had fallen. The evening sky was enveloped by dark clouds, fragmented by the enormous billboards along the highway, and the familiar daytime scenery had become alien.

In the flickering lights, a Chinese restaurant came into view, and I found myself drawn to it as if pulled by an invisible force. I vaguely remember water droplets condensed on the restaurant’s windows, and the interior decor was indistinguishable from any other Chinese restaurant in America. Despite my digestive system suffering from the cold, bland Western food, it hadn’t occurred to me, on my first trip abroad, to search for Chinese restaurants. If not for the chance of getting lost after getting off the bus, I might never have realized I had this option. During my three months in the small town of Eugene, I didn’t even know there was a river outside the school, nor could I accurately point out which beach housed the sand dunes we visited for field research in my design class. Although later interactions with friends gradually eased my sense of loneliness, the city remained a blur to me; I felt more like an involuntary stranded traveler than a resident.

The restaurant was called Maple Garden (it’s no longer on the map now). I ordered a bowl of hot and sour soup and a plate of fried rice with salted fish and diced chicken. As I swallowed the rice with the hot soup, I told myself: At least next time when I’m feeling down, I can come here for a warm meal. I never went back after that time, probably because the food quality was unremarkable. But on that day, after spending more than two hours on the bus and being forced to kill three hours at Walmart, a warm meal at this Chinese restaurant in a foreign land gave me a sense of home.

片段一:尤金小镇的中餐厅

2013年秋天我第一次出国,在美国俄勒冈大学交换(彦祖毕业于此)。学校位于俄勒冈州的尤金小镇上,该小镇以耐克诞生地和俄勒冈大学橄榄球队的吉祥物鸭子闻名,学校的官网上也赫然写着“我们是鸭子(We Are Ducks)”。交换的时候分配的学生宿舍里没有厨房,校园里也没什么中餐,所以我基本都靠公寓楼下的沙拉菜加照烧豆腐或鸡胸肉果腹。

一个普通的周末,我坐了将近一个小时的巴士去到一家城郊的沃尔玛。校园之外的世界就像是一个巨大的旷野,没有城市、没有行人,只是大片的玉米地,这些玉米地串起学校和沃尔玛这样的文明中心。然而我并不知道的是,镇上周末的巴士一小时一班,买完东西出来的时候我正好错过前一班车,无奈地被迫又回去沃尔玛逛了45分钟。再次出来的时候万幸坐上了下一班车,然而到学校的时候已然夜幕降临, 天空的晚霞被乌云裹挟,又被公路旁硕大的广告牌分割开来,白天熟悉的街景也变得陌生起来。

闪烁的灯光中映出一家中餐厅,我像被什么东西牵着一样走了进去。依稀记得餐厅的窗户上凝结着水珠,室内的陈设和所有美国的中餐厅无异。第一次出国的我虽然胃肠饱受冰冷白人饭的折磨,可竟然没想到搜索一下中餐厅,如果不是下车迷路的这个契机,我可能永远都没有意识到我还有这样一个选择。在尤金小镇的三个月时间,我甚至不知道学校外面有一条河,我也无法准确地指出设计课去地段调研的沙丘究竟在哪个海边。虽然之后和朋友们的相处让我逐渐摆脱了孤独感,但这个城市对于我来说是模糊的,我更像一个被迫滞留的旅客。

餐厅叫枫林小馆(现在地图上已经找不到了),我点了一碗酸辣汤和一份咸鱼鸡粒炒饭。米饭就着热汤下肚的时候,我对自己说:至少下次不开心的时候,可以来这里吃个热饭。那次之后我再也没回去过,估计也是因为菜的质量平平无奇,但是在那个坐了两个多小时大巴,在沃尔玛被迫滞留三个小时的一天,一顿异国中餐厅的热饭给了我一种家一般的感觉。

2 | Pandemic Cycling Diary

Our perception of urban spaces is influenced by our mode of transportation. The accessible range and sensory cognition at a walking speed of 5km/h differ significantly from those at a driving speed of 120km/h. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States in 2020 and lockdowns began, public transportation came to a standstill. Although there was a subway station right below my apartment building, I hardly ever used it. Like many others without a private car, I felt trapped. The parks within walking distance were few, and after visiting them a couple of times, they no longer held any novelty.

By chance, a friend of mine was stranded in China due to the pandemic, and I acquired her bicycle (Little Yellow) as a means of transportation. From that moment on, my city map opened up. I replaced the public transportation layer on my map with a cycling layer. On many evenings after work or on weekends with good weather, I would randomly select blue or green areas on the map, zoom in a bit to make sure it wasn’t a cemetery or a golf course, and then embark on spontaneous cycling trips.

I began to discover various greenway systems in Boston and the surrounding cities. I learned that the greenways along both sides of the Charles River span three cities (Boston, Watertown, Waltham) with a total length of 37 kilometers. The Southwest Corridor, which connects Jamaica Plain and Back Bay, was originally planned in the 1960s as a 12-lane highway. At a time when countless communities across America were being razed for interstate highway construction, protests from this community halted the plans for Interstate 95. After numerous meetings, it was ultimately transformed into a linear greenway that integrates subway lines, parks, bike paths, and community centers.

Some of these greenways run alongside railway tracks, while others traverse community centers, bordered by the backyards of private residences. They offer new cross-sections of the city, greatly expanding my footprint. Once, a friend and I even cycled a round trip of 40 miles from Cambridge to Nahant Beach. On our way back, we encountered thunder and lightning, forcing us to take shelter under an unfamiliar bridge pier. Catalyzed by the pandemic and aided by Little Yellow, I may have reached the athletic peak of my life as a sports novice. I also witnessed landscapes within the city that were close by yet had never revealed themselves to me before.

(https://southwestcorridorpark.org/history.asp)

片段二:疫情骑行日志

我们对于城市空间的感知受交通方式的影响,5km/h的步行速度和120km/h的车行速度下人的可达范围和感官认知是不一样的。2020年美国疫情爆发开始封城之后,公共交通瘫痪。虽然地铁站就在我公寓楼下,我却基本没坐过。没有私家车的我和许多人一样觉得自己被困住了,步行可达的公园就那么几个,去几次就毫无新鲜感了。

机缘巧合,朋友因疫情被困在国内,我从她那里获得了一辆代步自行车(小黄),从此我的城市地图就被打开了。地图上原本的公共交通图层被我换成了自行车图层。在很多个下班的傍晚或者天气好的周末,我随机选择地图上蓝色或者绿色的区块,稍微放大一下确认不是墓地或者高尔夫球场,然后就开始说走就走的骑行。

我开始接触到波士顿以及周围城市的各种绿道系统,知道查尔斯河两旁的绿道跨越三个城市 (Boston, Watertown, Waltham),全长37公里。连接Jamaica Plain和Back Bay的西南走廊 (Southwest-Corridor) 在1960年代的时候被规划为一条12车道的高速公路,在全美无数社区因州际高速公路建设而被夷为平地时,该社区的抗议活动使得95号州际公路的计划搁置,并最终在无数次的会议后变成了集地铁、公园、自行车道、社区中心为一体的线性绿道。

这些绿道有的在铁轨旁边,有的穿越社区中心、两边接邻着私人住宅的后院。它们提供了新的城市剖面,使得我的足迹大大拓展了。甚至有一次我和小伙伴从剑桥骑车来回40英里去了Nahant海滩,回来的路上电闪雷鸣,不得不在一个不知名的桥墩下躲雨。在疫情的催化和小黄的助力下,我可能达到了一个运动小菜鸡这辈子的巅峰,也看到了城市里那些离我很近却从未展露的风景。

3 |First Week in Sheffield

Just when I thought I was going to be a long-term resident of New England, I received an admission notice last spring, unexpectedly starting a new life in an unfamiliar country. Unlike my previous experience of flying to Oregon without any prior knowledge, this time I needed to rent an apartment in advance. I spent time early on checking various student apartments on the map, measuring their distances from the school and Chinese supermarkets. To have more time to get to know the city, I arrived in Sheffield two weeks early.

The first day was a classic opening for international students: pouring rain, me struggling with three suitcases, and finally reaching the apartment only to find that the supposedly furnished flat was completely bare. While communicating with the apartment management, I rushed to the Chinese supermarket to buy necessities. The moment I filled the refrigerator with familiar foods, I felt I could survive here! I can survive here!

Within the first week, I bought a second-hand trolley. I then went around various student apartments, wheeling my trolley among Chinese international students, buying second-hand daily necessities. Along the way, I noted down street names, locations of supermarkets and restaurants, adding stars on my map. Later, I discovered the Moor, a comprehensive market that combines a vegetable market, butcher shops/seafood market, food court, nail and beauty services, and a market for small commodities from Yiwu. The vendors with heavy Northern accents affectionately call customers from just-of-age to eighty “love~”, and greet with “Ey Up!” instead of “Hello!”. Here, one can truly feel why Sheffield is called the “Big Northeast” of England.

Subsequently, I spent almost every free weekend exploring different areas, not content with the routine of just shuttling between school and apartment. I yearned to establish a deeper connection with this city, so each weekend I tried to set off in a new direction. Sometimes I would experience the artistic district of converted industrial warehouses in Kelham Island, other times I would document various street art and graffiti throughout the city. Occasionally, I would take a bus or train to randomly arrive at a small town in the Peak District National Park, embarking on a day’s hiking trip, looking back at the skyline of this old industrial city from different heights and angles, where factory chimneys coexist with modern architecture.

A year is a short time, and merely walking these places doesn’t make me a local. There’s still a long way to go from knowing where to find things for daily life to feeling like I belong to this city. Cultural identity is perhaps more important than spatial cognition. But at the same time, I believe that a sense of belonging is the result of practice, and each exploration demonstrates my proactive attitude in embracing this city.

片段三:初到谢菲尔德的一周

本来以为就要在新英格兰地区常住的我去年春天收到录取消息,竟然又要开始一个陌生国度的生活。和当初一无所知就飞往俄勒冈的我不一样的是,这次的我需要提前租房,于是早早就在地图上查看各大学生公寓,测量它们距离学校和中超的位置。为了有更多了解这个城市的时间,我提前两周就到了谢菲尔德。第一天到的时候简直是留子经典开局:天降大雨,拖着三个行李箱的狼狈的我好不容易到了公寓,发现预定的带家具的公寓竟然家徒四壁。一边和公寓沟通一边我又赶紧去中超买东西,当我把冰箱塞满了熟悉的食物的那一瞬间,我感觉我可以在这里生存下去了!I can survive here!

在来的第一周内收了个二手小推车,接下来便拉着小车游走在各大学生公寓的中国留子之中收购二手日用品,顺便记录街道的名字、超市、餐厅的位置,在地图上加上星标。后来我又发现了the Moor,一个集菜市场、肉铺/海鲜市场、美食广场、美甲美容、和义乌小商品市场于一体的综合市场。北部口音很重的摊主们把从刚成年到八十的顾客都亲切地叫“love~~”,打招呼不说Hello而是Ey Up!在这里能真切地感受到为什么谢菲尔德被称为英国大东北。

随后我基本每个有空的周末都在到处跑,不满足于学校和公寓两点一线的生活。我渴望与这个城市建立更深刻的联系,于是每个周末我都尽量选择一个新的方向出发,或是感受凯尔汉姆岛工业厂房改造的艺术街区,或是记录城市中各式各样的涂鸦,或是乘坐巴士/火车随机来到一个峰区国家公园 (Peak District) 的小镇,开始一天的徒步之旅,从不同的高度和角度回望这个旧工业城市烟囱与现代建筑并存的天际线。

一年的时间很短,我并不会因为走过这些地方就变成了当地人。从知道日常生活需要的地方在哪里,到觉得自己属于这个城市之间还有很长的距离,文化认同或许比空间认知更为重要。但同时我也相信,归属感是实践的结果,每一次的探索体现的是我主动接纳这个城市的姿态。

Migrant Newcomers and Ordinary Spaces

If we were to mark every place I’ve been to that’s important to me, the density of these markers on a scaled-down map would reflect my urban footprint. The process of transforming a completely unfamiliar city – a mere code or a media-symbolized image – into a city where I’ve lived and measured with my footsteps can be long or short, but it’s always accumulated through each experience. The seemingly repetitive commuting, shopping, and leisure activities imbue this general, abstract urban space with personal meaning: an ordinary café becomes “the place where I had a coffee chat with someone,” a common bench becomes the spot for watching fireworks on National Day. These markers become my anchors in this unfamiliar environment. Lines connect these base points, gradually weaving into an increasingly complete network. This network will become the foundation for the transition from mere survival to truly living, facilitating the shift from “I can survive here” to “I belong here.”

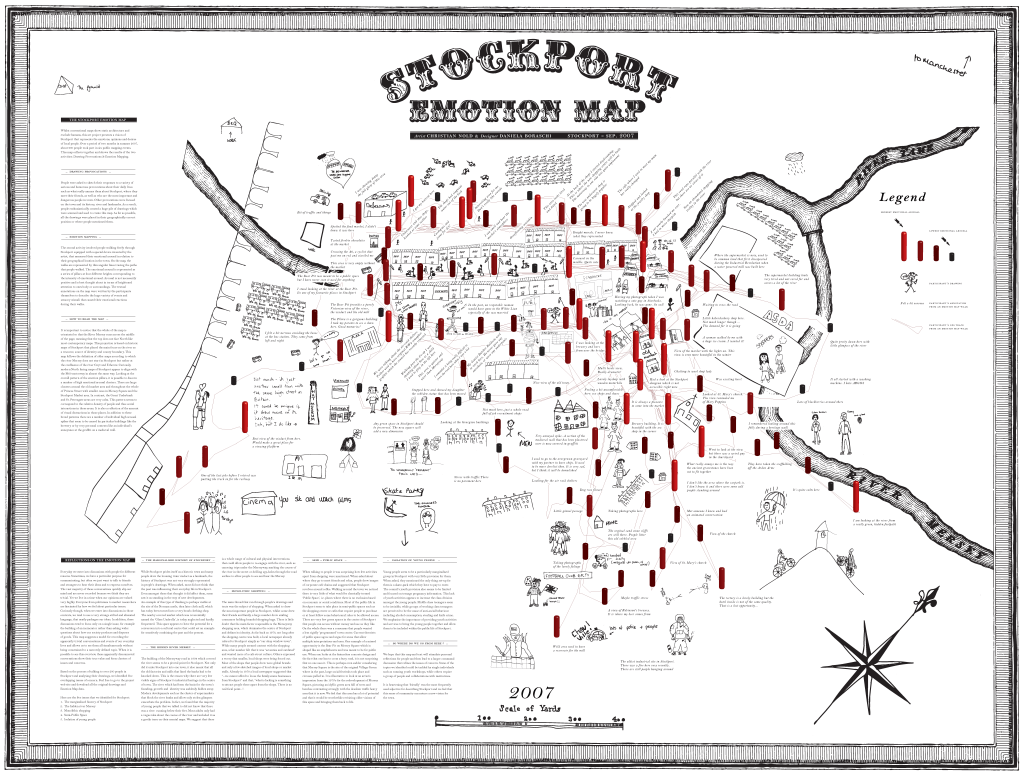

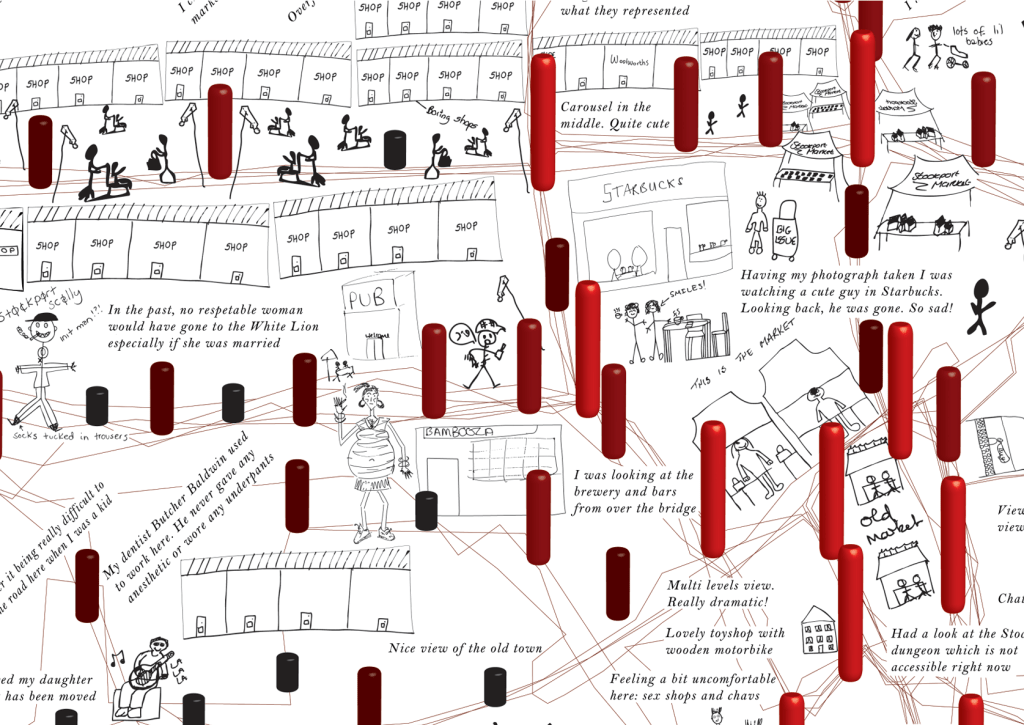

The three vignettes above are my city map, based on my background and specific life stage, composed of Chinese restaurants, supermarkets, parks, public transportation, schools, companies, etc. Other migrant newcomers, such as international students, foreign workers, migrant populations, refugees, etc., have different perceptions of the city and relationships with urban spaces. These relationships are influenced by other social labels such as nationality, gender, race, and beliefs. If each of us were to depict our daily trajectories over a few days, marking places that are familiar, safe, vibrant, dangerous, or inaccessible, these individual maps could be combined to form a certain group’s perception of urban public spaces. What I’m focusing on is not the difference between personal cognitive maps and the actual urban layout (like Kevin Lynch’s “The Image of the City”), but rather the result of repeated practices.

If we consider urban space as a resource, then an individual’s city map reflects the collection of resources available for them to organize, as well as the result of their organization of these resources. In this process of gradually expanding the map, personal agency and environmental affordance¹ work together. The distribution of spatial resources in cities is inherently unequal, and the spatial range each person can access is limited. Many past studies have used communities as the unit of analysis, revealing the springboard effect of immigrant communities and the potential formation of ethnic enclaves (concentration of ethnic minorities in certain urban communities). These studies often overlook human mobility, focusing solely on the residential perspective while neglecting new urban spatial experiences brought about by work and leisure activities. Studying this broader, more continuous urban map might reflect needs that cannot be met within the community, revealing tactical rebellious behaviors (tactics)² of individuals under spatial constraints. These behaviors may include finding alternative paths, redefining the purposes of spaces, or creating new social networks to adapt to and overcome various limitations and challenges in the urban environment.

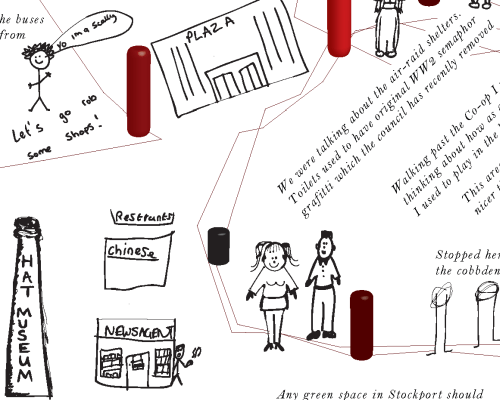

Designers: Christian Nold, Daniela Boraschi

This is a two-month participatory mapping project that reconstructs the city through the eyes of its residents using participants’ hand-drawn maps and interviews. (http://www.softhook.com/stock.htm)

When we first arrive in a new city, we carry our phone maps everywhere, cautiously navigating to avoid getting lost. Everything is fresh yet unfamiliar, and we need to go through a learning process³, gradually forming fixed life trajectories, establishing new spatial and social relationships, completing the transformation from traveler to resident. This process is not only influenced by our personal agency and spatial cognitive abilities but also depends on the degree to which the city’s resources are open to us, as well as the attitudes of other residents towards us. The distribution of resources, their accessibility, and group acceptance can all lead to structural inequalities, which may be amplified by special events (such as pandemics or natural disasters).

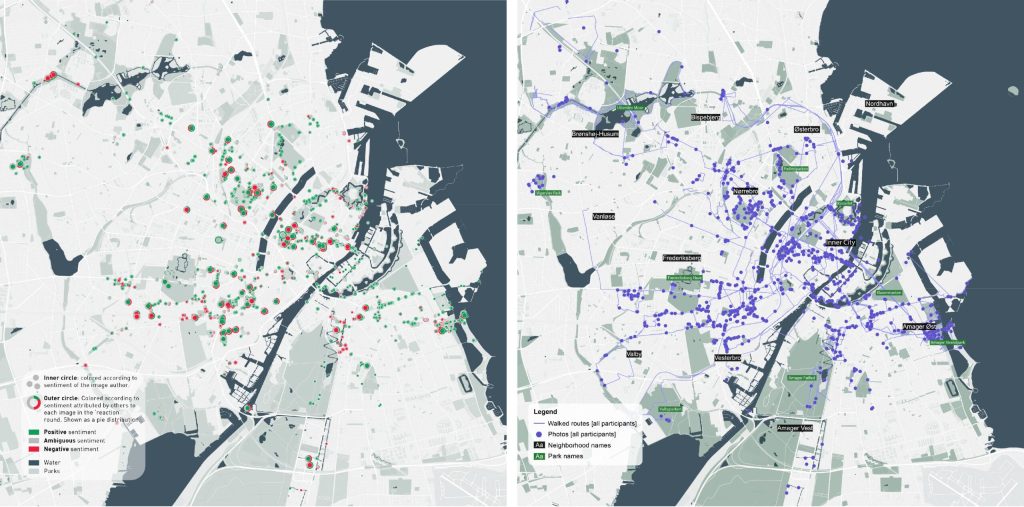

This project innovatively employs citizen participation methods, inviting participants from LGBT+, deaf, homeless, international, ethnic minority, psychologically vulnerable and/or physically disabled communities. It uses participatory geographic information systems (GIS) and a newly developed open-source Photovoice application specifically for the project to record their experiences of belonging in Copenhagen. (https://urbanbelonging.com/en)

What I want to study is this process of “arrival”⁴, exploring how urban new immigrant groups establish more profound relationships with urban spaces through spatiotemporal slices of daily life. I aim to analyze each person’s city map-making process from the perspectives of the publicness of public spaces and the inclusivity of cities. Possible research methods include participatory observation, space-time activity diaries, walking interviews, and spatial data analysis. The research results aim to elucidate the process by which some urban new immigrants establish factual and emotional connections with urban spaces, as well as the role of urban design and planning in this process. It reflects an important issue of our time: in an increasingly globalized and mobile world, how do we create urban spaces that allow everyone to feel a sense of belonging?

城市新移民与日常空间

如果给每一个我去过的、并且对我来说重要的地方都打上标志,那么在缩小的地图上就可以通过这些标记的密度体现出我的城市足迹。从一个完全陌生的城市、一个代号,或者是一个被媒体符号化的图像,到一个我生活过、用脚步丈量过的城市,这个过程或长或短,但都是通过每一次的体验所累积的。看似重复性的通勤、购物、休闲娱乐,它们赋予了这个笼统的、抽象的城市空间以个人意义:一间普通的咖啡厅变成了“我和张三 coffee chat的地方”,一个普通的长椅变成了国庆节看烟火的地方。这些标记成为了我在这个陌生环境的锚点 (anchor),由这些基点连成线,继而织成一个逐渐完善的网络。这个网络将成为由生存到生活的基础,由此发生从“我能生存下来”,到“我属于这里”的转变。

以上的三个片段是我的城市地图,基于我的背景和特定的人生阶段,它们由中餐厅、超市、公园、公共交通、学校、公司等组成。其他的城市新移民,比如国际学生、外来劳工、流动人口、难民等,他们对于城市的感知、与城市空间的关系是不一样的,并且该关系受到其他社会标签,例如国籍、性别、种族、信仰等的影响。如果让我们每个人描绘一个几天的日常轨迹,并且标示出熟悉的、安全的、有活力的、危险的、不可进入的的地方,个人的地图就可以集合成某一个群体对于城市公共空间的感知。我所关注的并非个人的认知地图和城市真正布局之间的差异(例如凯文·林奇的《城市印象》),而是重复实践的结果。

如果说城市空间是一种资源,那么一个人的城市地图就体现了可供他组织的资源的集合,以及他组织这个资源的结果。在这个逐渐扩展地图的过程中,个人能动性 (agency) 和环境可供性1(affordance, 也被翻译为环境赋使)共同作用。原本城市中空间资源分布就是不平等的,每个人接触到的空间范围亦是有限的。过往的许多研究都以社区为分析单元,揭示移民社区的跳板作用以及可能形成的民族飞地现象 (少数族裔在城市中聚集在某一个社区)。这些研究往往忽略了人的流动性,仅仅从住宅的角度出发,而忽略了工作、娱乐活动等带来的新的城市空间体验。研究这个更为广阔的、更有连续性的城市地图或许可以反映社区内部无法满足的需求,反映个人在空间限制下的战术性反叛行为 (tactics)2。这些行为可能包括寻找替代路径、重新定义空间用途,或创造新的社交网络,以适应和克服城市环境中的各种限制和挑战。

最开始刚到一个新的城市时,我们到哪里都拿着手机地图,生怕迷路因而小心翼翼。一切都是新鲜的,也是陌生的,我们需要经历一个学习的过程3,继而逐渐形成固定的生活轨迹,建立新的空间和社会关系,完成从旅客到居民的转变。这个过程并非只受我们个人能动性和空间认知能力所影响,也取决于这个城市的资源对我们的开放程度,以及城市里的其他居民对我们的态度。资源的分布、资源的可达性、群体的接受度等都可能带来结构上的不平等,并被特殊事件放大(例如疫情、自然灾害)。

我想要研究的,就是这个“到达” (arrival)4 的过程,通过日常生活的时空切片去探究城市新移民群体与城市空间建立更为深刻的关系的过程,从公共空间的公共性,以及城市的包容性的角度去分析每个人的城市地图绘制过程。可能的方法诸如参与式观察、时空活动日志 、行走访谈法、空间数据分析等。研究的结果希望阐释部分城市新移民与城市空间建立事实和情感联系的过程,以及城市设计和规划在其中的作用。它反映了这个时代的一个重要议题:在日益全球化和流动的世界中,我们如何创造能够让所有人都感到归属的城市空间。

References:

1: Gibson, J.J. (1986) ‘The theory of affordances’, in The ecological approach to visual perception. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, pp. 119–135.

2: Certeau, M. de (1984) The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

3: Buhr, F. (2018) ‘A user’s guide to Lisbon: mobilities, spatial apprenticeship and migrant urban integration’, Mobilities, 13(3), pp. 337–348. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2017.1368898.

4: Meeus, B., Arnaut, K. and van Heur, B. (eds) (2019) Arrival Infrastructures: Migration and Urban Social Mobilities. 1st edn. Cham: Springer International Publishing : Imprint: Palgrave Macmillan. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91167-0.